History of the Mace

The head of the Mace has a winged lion carrying a trident on its shoulder.

The Mace of Singapore

The lion is the symbol of Singapore and from which the State derives its name. The wings represent the city's importance as an air centre and the trident was the symbol of the city's maritime trading centre for ships from all over the world. On the shaft directly below the lion figure, are the crest of the British Crown on one side and the crest of the Colony on the other.

At the base of the shaft is a ring of fish sporting among the waves. The shaft is embossed with lion heads and Chinese junks at regular intervals.

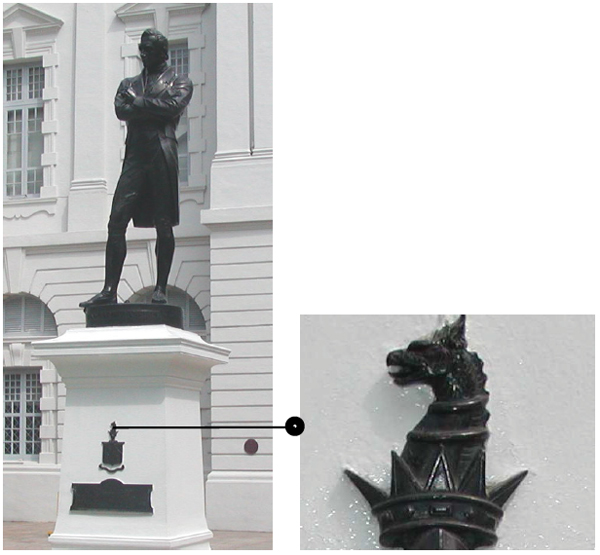

Set at the base of the Mace butt is Sir Stamford Raffles' family's coat of arms; an image of a gryphon head over a royal crown within a round band.

The same coat of arms is found on the pedestal of Sir Stamford Raffles' statue at Empress Place (Singapore).

The Medieval Mace

During medieval times, the mace was a weapon used by warriors in close combat during war to break the chain mail or body armour of opposing knights.

During this period in England, the King’s bodyguards were known as Serjeants-at-Arms and they all carried maces. The Royal Serjeants-at-Arms were mainly tasked to arrest offenders and summon subjects to appear before the King. The Serjeants were always armed with their maces whenever they carried out their royal duties, and their maces were gradually regarded as the symbol and warrant of the King’s authority. To distinguish the King’s Serjeants from other common warriors, the butts of the Serjeants’ maces were stamped with the Royal Coat of Arms. As few people then could read or write, the royal coat of arms on the mace was sufficient for people to recognise it as a symbol of the sovereign’s power and authority. The mace bearer is also recognised as a representative of the sovereign and people had to obey them accordingly. Over time, the mace became more of a symbol of royal authority than a weapon.

Ceremonial and Other Duties

Serjeant-at-Arms

The Serjeant-at-Arms plays an important role in Parliament. He bears the authority of the Speaker of Parliament.

At the commencement of each Parliament sitting, the Serjeant shouldering the Mace leads the Speaker, the Clerk of Parliament and the other Clerks into the Chamber. He sits in the Chamber throughout the session to wait for the Speaker's orders.

In the event of a disturbance in the Chamber or Public Galleries, the Serjeant will act under the Speaker's authority and ensure that the person(s) responsible for the disturbance is/are removed from the premises. If a member of public is required to present himself/herself before Parliament or a Parliamentary Hearing Committee, the Serjeant will execute the Speaker's warrant, commonly known as 'summons', to the required person to appear before the committee.

By tradition in the Commons and here in Singapore, the Serjeant-at-Arms controls the access of all persons into the House. This includes all staff and visitors and responsibilities of such nature are managed by issuing security passes and Admission Orders for Parliament sittings.

The Serjeant also performs other traditional duties such as attending to protocol duties, Speaker's directions and other tasks assigned by the Clerk of Parliament.

As the Serjeant’s duties involve elements of security concerning the Speaker and Members of the House, he is positioned in the Security Department.

The Ceremonial Drill

In the formal chamber setting, there was no precedent on the ceremonial drill and the placement of the Mace when the Legislative Assembly was formed.

Understanding the need for such formalities, the Clerk of the Legislative Assembly, Mr Loke Weng Chee, wrote to his counterparts in other Commonwealth countries to enquire about the drill. He then compiled notes on the drill and forwarded it to Speaker George Oehlers, who decided on the adaptation of the procedures. Through trials and errors, the then Serjeant-at-Arms, Mr Mahmood bin Abdul Wahab perfected the drill.

The Mace drill has three sequences, namely, at the commencement of sitting, when the House goes into Committee, and at the suspension of a sitting. In all three sequences, the Serjeant-at-Arms, when not carrying the Mace, shall bow twice, once at the Bar and second, at the end of the Table of the House before he lifts the Mace or when he places the Mace on the Table. Before he returns to his desk he shall bow (after placing the Mace on the Table) and again when he is at the Bar (facing Speaker) before he returns to his desk.

At the Election of Speaker

Until the new Speaker of Parliament is elected, the Mace is not placed on the Table during the first session of a new Parliament.

Prior to the commencement of the session, the Serjeant will place the Mace on the brackets beneath the Table. After the new Speaker is elected and has taken the Chair, the Serjeant will proceed to place the Mace on the Table.

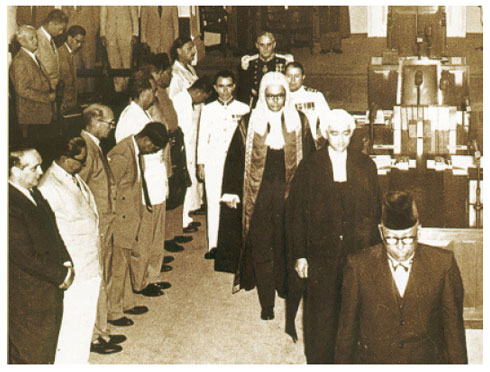

President’s Address to New Parliament

At the Opening of a new Parliament, the Serjeant, without the Mace, precedes the Clerks (the Clerk of Parliament, the Deputy Clerk and a Principal Assistant Clerk), the Speaker and the President in that order, into the Chamber. The President is flanked by his aide-de-camps in front and behind him.

The Deputy Serjeant-at-Arms may stand-in for him.

The Mace Committee

During the run-up to the formation of the Legislative Council, the then Governor of Singapore, Sir John Nicoll, set up a Committee comprising Legislative Councillors, Mr N A Mallal, Mr John Laycock, Mrs Elizabeth Choy and himself to look into the provision of a mace for the future Legislative Council.

The committee decided that the design of the future Mace should incorporate Singapore's history, national symbol and strategic importance as an air and seaport. In early 1954 when Sir John Nicoll visited London, he contacted Mr Leslie Durbin, a silversmith and discussed the making of the mace.

Mr Durbin made a sketch of the proposed mace, and incorporated the design decided by the committee. The most outstanding feature of the proposed mace was the head which had a figure of a lion. Mr Durbin proposed that he would make the shaft and a reputed sculptor be engaged to craft the lion figure for the head of the mace. He recommended a renowned sculptor who agreed to a sum of 1000 guineas1 for the job.

On 22 February 1954, the Rendel Commission Report was published and on 15th June 1954, as the Governor of Singapore, Sir John addressed the Legislative Council and said that the successors in the future Legislative Assembly would have a Speaker and a Mace.

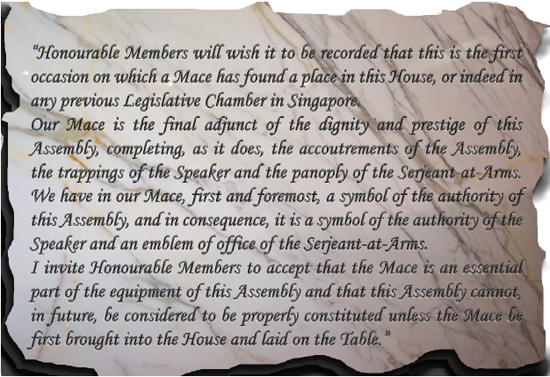

On 20th July 1954 , Sir John said in his address before the Legislative Council:

11000 guineas is equivalent to roughly $9,215 today